What follows are versions of chapters in How to Succeed in College and Beyond: The Art of Learning (Wiley-Blackwell)

BEGINNINGS

The College Olympics: How to Choose the Right College and How to Get the Right College to Choose You

17 Suggestions for Choosing Classes in College

THE COLLEGE EXPERIENCE

Twenty Suggestions for Incoming College Freshmen

Nineteen Suggestions for College Sophomores

Suggestions for College Juniors: Balancing the Joy and Practicality of Learning

Making the Most of Your Senior Year in College

Suggestions for Seniors Graduating From College: Planning for the Future

Changing the World: Are college students less idealistic than they were in the Sixties?

How to Succeed at College and Beyond: The Art of Learning

THE CASE FOR THE HUMANITIES

What to Do With a B.A. in English?

Why Study the Arts and the Humanities?

Do the Humanities Help Us Understand the World in Which We Live?

WHAT PROFESSORS DO?

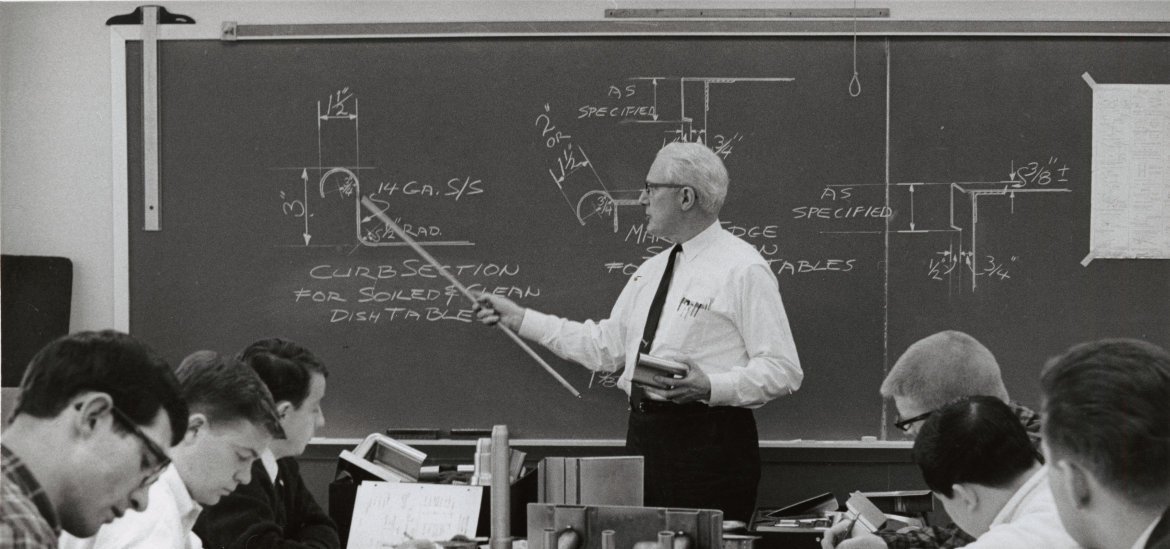

Are Teaching and Research Mutually Exclusive?

Teaching Freshman Humanities at Cornell: Toward a Community of Inquiry

My Guest Columns from the Cornell Sun

Should a Lottery be Added to the Admission Process?

The Function of the University Classroom

How has English Studies Changed

The Significance of the Oct. 7, 2023 Hamas Atrocities

Further Thoughts on the Hamas-Israel Conflict

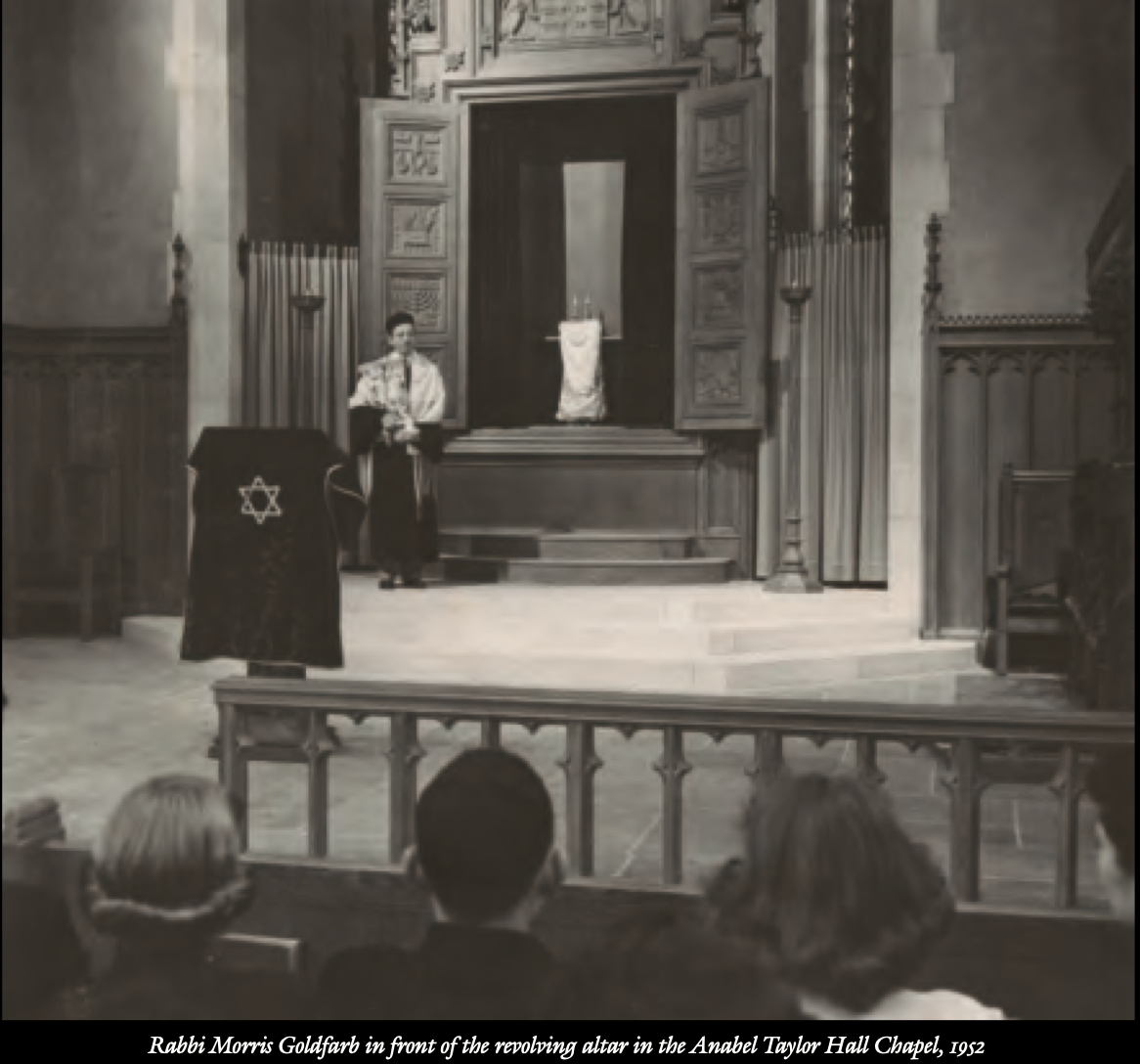

Anti-Semitism at Cornell and Beyond: Then and Now

How We Learn from Our Students

The Israel-Hamas War and the Effect on the American Jewish Experience

Remembering Teachers Who Mattered and Are Part of Who I am Today

How to Prepare for College

Introduction:

Because I have been teaching at Cornell for more than four decades, and because I have been writing on Higher Education for the Huffington Post and in 2008 published In Defense of Reading: Teaching Literature in the Twenty-First Century, I am often asked if I have any suggestions for preparing for college. The following suggestions are by no means inclusive but provide some basics.

A student needs to develop the necessary skills to pursue a college degree, although in truth there are many kinds of colleges and some are far more difficult than others, both in terms of admittance and performance expectations. Not every one is thinking about an elite college. For many the right choice is a local branch of a state college, a community college for the first two years, or a good but less selective small liberal arts college, none of which have the rigorous entry requirements of the Ivies, MIT, Caltech, Chicago, Stanford, Duke, Northwestern or the major State Universities (Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, UCLA, Berkeley, etc) or the elite small liberal arts colleges (Amherst, Williams, Middlebury, Emory, the Claremont schools, etc).

Before choosing a college, students need to consider why they want to go to college and what they expect to get out of it. Student should think about the relative emphasis they put on learning skills for a job, on preparing for graduate education, and on pursuing the liberal arts. (See my "What to with a B.A. in English?")

Part of college preparation is figuring out the costs. The elite colleges are the most heavily endowed, but other schools may offer a particular student a more generous financial aid package in order to attract him or her for either athletics or academics. Taking enormous loans may be a less desirable path than going to an in-state college.

What Can Parents Do?

Putting away funds for college beginning soon after a child’s birth is an excellent plan, and many states give tax benefits to those who do so under 529 plans. Asking children to earn some money for college while in high school and college is reasonable. But students should not be asked to sacrifice their schoolwork or, if at all economically feasible, their participation in school activities. Working in summers will give students valuable experience while giving them a chance earn funds for college

The more positive the home environment, the more likely a child will succeed in school. When parents take an interest in their children’s day-to-day learning in school, children respond. But interest does not mean doing, and children need learn to do their own work and turn to parents only after they have made a strong effort on their own. Not every parent will be able to help with advanced high school math and physics, but those who can help should focus on teaching the concepts rather than doing the problems.

Preparation for college should begin early. Parents need to play a motivating role, and we know that educated parents are more likely to produce educated children. But we also know that successful students -and those that in ensuing years make a significant difference in their fields-come from every socio-economic and ethnic background and that emphases on learning within homes can take place even in tightened circumstances in rough neighborhoods.

Parents should monitor how their children spend their time and can do this from an early age. They need to be alert to their children’s mental and physical health, and face head on issues of depression, learning disabilities, and physical limitation. They need to be aware of the people with whom their children spend time. If parents smoke and drink and abuse drugs, their children are far more likely to do so.

Parents should stress the pleasures of reading-the exaltation of reading a great book-and insist on quiet time as well as regulate TV watching to a set number of hours per week. Parents can expose their children to cultural opportunities: theatre, music, museums, etc. If these are not readily available-to some degree they usually are- -trips to even small cities can complement rural villages and towns.

While parents should encourage participation in sports and the development of specific skills in the sports that children choose, they should also make their children aware of how few people make their living as professional athletes. It should be obvious that being the best player on a high school team usually does not result in making a livelihood in a sport.

Secondary Schools

High schools have different cultures, and those that focus on academic achievement are usually the best ones to prepare students for selective universities.

If the situation demands it, parents can in some areas enroll their children in public schools with a more favorable learning culture than the ones closest to their home or, if this is not possible and funds permit, enroll in a private school, some of which do offer scholarships to those in need.

Some schools give students major advantages in college preparation and in the admission process. But the elite colleges seek geographic and ethnic diversity and find students from all over the country. Special public schools that select students by means of a rigorous test are called Magnet Schools; they include Stuyvesant, Hunter and The Bronx High School of Science in New York, Boston Latin, Classical High School in Providence, the School for the Talented and Gifted in Dallas. Other alternatives are elite private boarding schools such as Exeter, Choate, or Andover or day schools such as Dalton, Horace Mann, or Fieldston in New York; the National Cathedral School in DC; Germantown Friends School in Philadelphia; and Harvard-Westlake school in Los Angeles.

What Students Can Do

It is never too early to think about what kind of career you want to have and to begin learning what kind of preparation is necessary for that. Speaking to people about their careers and reading about what people do are ways to develop a sense of what is right for you. If you are fortunate, your work will bring you joy and satisfaction. Knowing whether you want to be a doctor, a lawyer, engineer, business executive, CPA, teacher or college professor may help shape your HS curriculum and your choice of colleges, but developing the skills I mention below will be helpful to whatever career you choose.

To succeed in higher education, you need to develop time management and disciplined study habits as early as middle school. It is a good idea to keep track in writing or keep a computer file of how you are using your time. You need to set aside specific times for study and during those times you should turn off the TV and put the smart phone away. Realistically, you might begin with 30 to 40 minute study periods but by your later high school years you should be able to concentrate without a break for between 60 to 90 minutes.

The best preparation is to learn how to read carefully and thoroughly whether it be fiction or non-fiction; the latter category includes newspapers in print or on line. Select your reading with discrimination and rely on suggestions from teachers and other well-read adults. It is important that you keep up with national and international news and issues and that you develop an interest in the world in which you live, including the rapidly changing world of science. Reading the New York Times, the best news source in the US, for a half hour daily will help.

Reading well means reading skeptically and learning to find places in newspapers or online when arguments are not logical or require more imagination. Developing a critical intelligence is a crucial component of learning.

Equally important to reading intelligently is developing your writing skills. That means taking every writing assignment seriously. It means learning to write drafts, and that requires beginning assignments as soon as they are given. Term papers can teach you how to do research and use the library and internet as research tools.

Writing takes constant and continuing practice. Keeping a journal or diary, providing you stress writing well when doing so, is a good way to practice writing. I would buy-and read once a year-Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style.

You also need to develop listening skills in class, and that means getting enough sleep. Taking notes in class will help you develop listening skills and also will help you organize material, which is essential not only for test taking but for understanding any subject. If you are permitted to bring a computer to class, take notes on that. Keep a separate file for each course and continue to re-organize as the semester progresses. Remember that you can always edit material if you write down too much, but you cannot recoup material that you have forgotten. If you miss class, borrowing another student’s notes is essential. But always be sure to borrow from top students.

Finally, and this needs be stressed, you need to develop verbal skills and learn to play a significant role in class discussion. You should speak in class even if it takes effort. Making notes to yourself about what you want to say before you raise your hand helps many students overcome reluctance to speak in class. Try to eliminate “mmm”s and “you know”s when you speak in class and think of your class contributions as relatively important events.

Learning How to Learn

To prepare for college, high school should be a challenge and an opportunity. Working hard is the best preparation. Developing curiosity, a desire for knowledge, and the ability to solve complex thought-provoking problems are important life skills.

Studying well is a matter of learning how to concentrate and block out everything else. Most people do better when not listening to music, but some people seem to be able to listen to soothing music when studying. Using study halls and homeroom to study rather than wasting time on video games or social media is a good way to be time efficient.

When it is permitted, studying with a classmate can be helpful, but you must choose wisely and keep focused on the work at hand and not on other matters. Indeed, choice of friends is an important ingredient of school success, and if your social group is motivated to learn, the chances are better that you will be, too.

Take challenging courses, including basic sciences and math courses even if that is not your primary interest. In computing rank and grade point average, many high schools give extra quantitative emphasis for advanced and honors courses. Colleges not only consider the difficulty of high school programs when weighing students’ applications, but succeeding in difficult courses will be the best preparation for the next educational challenges. Without high school biology, chemistry, and physics and college preparatory math and/or calculus as well as computer science, you will not be able to begin to understand the world in which you live. Furthermore, by not taking such classes you foreclose some of your future options in pursuing sciences and engineering. (You might read Steve Strogatz’s The Joy of x). Moreover, colleges expect you to have basic knowledge in those areas, even if you ultimately study the humanities, social sciences, or a business curriculum.

Even now when English is becoming the basic language of the world, it is important to study a foreign language. For one thing, it will help you understand the world better because you will learn something about another culture, and for another you will be preparing yourself for some choices if you decide to do a junior year-or junior semester- abroad.

Be alert about who are the best teachers, and take advice from the best students. Great teachers are demanding in terms of standards, but also create an environment where students experience learning as a privilege and a pleasure. Getting to know some of your teachers well will give you the necessary sources of recommendations for your applications. Getting to know the advisor or guidance counselor who prepares the material transmitted to college is essential. When possible, take advanced placements courses and/or courses in a local college.

Other Suggestions

Participate in extra curricula activities such as varsity sports, school newspaper, drama and choral groups, orchestra and band, debating, and student government. Developing skills and competence in these areas builds self-confidence. High school is more rewarding, fulfilling, and fun for those who are part of the school community. Moreover, selective colleges favor for admittance those who play a leadership role in such activities, in part because such activities at a more advanced level play a vital role in college life and in part because the best advertisement for a college are alumni playing a leadership role in their communities and perhaps on the state and national level.

College admissions people are favorably impressed with those who are active participants in the community beyond school by volunteering to tutor or read to adults or work with disabled children or give some time at the local hospital or hospice. That volunteerism can be connected with your church or synagogue. Meaningful summer and after school paid jobs such as working as counselor for younger children or in a hospital lab can also be a plus for admission officers.

Nothing is more important for high school success than physical and mental health. Getting a full night’s sleep, eating properly, and avoiding cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs will enhance your enjoyment of life and your success in your studies. No matter how dedicated you are to a project, you need to take some time for fun activities. Each day you need to do something you like whether it be a walk in the woods, a visit to a museum, watching your favorite TV show, or pursuing a hobby.

Conclusion: Preparation for the Application Process

Standards tests such as SAT and ACT play an important role in admission. Particularly in highly competitive areas, high school students pay for special preparation classes or hire a private tutor to prepare for these tests, and these classes can be costly. Competitive high schools often stress preparation for these tests.

In the spring and summer of your junior year, you should begin to visit campuses in which you are interested. But you should begin learning about what colleges are for you even earlier. Interview processes vary but they seem to play less of a role than they once did and most public universities eschew them.

Although the college application and admission procedure is stressful, it is important to remember that where you do your undergraduate work is far less important than enjoying high school and college, while discovering the joy and privilege of learning.

“How to Prepare for College,” July 13, 2014,Huffington Post,http://t.co/pbYR1ezXwfvia@HuffPostCollege

The College Olympics: How to Choose the Right College and How to Get the Right College to Choose You

I have been blogging forHuffington Poston Higher Education for a few years and have been given a contract to write a short book tentatively titled:The Joy and Practicality of Learning: Succeeding in College and Beyond.

What follows is a sequel to "How to Prepare for College" and "Nineteen Suggestions for College Freshmen."

Finding the right fit for college is a complex process requiring considerable effort.

1) Find a match between your interests and the schools you apply to.You need to decide whether you prefer a rural or urban environment, whether distance from home is important, whether you wish to go to a school that foregrounds your particular religion, whether the size of the enrollment matters, and whether you want a true campus experience where students live on campus and near classrooms. You want to learn about the size of classes, whether they are taught by senior faculty or adjuncts and teaching assistants, and whether undergraduates--especially in the sciences and engineering but also the in the social sciences and the humanities--have a chance to do advanced research. You might also think about the physical facilities and the activities that interest you. You wouldn't go to the University of Florida if skiing were an important activity.

2) Find a match between your high school record and abilities and the schools to which you apply. You can find out whether your grades, rank in class and SAT and/or ACT scores meet the qualifications of the schools that interest you. Standard tests are a way that colleges get data that shows them whether an A in one school equals an A in another. But some diligent and imaginative students do not test well and are at a disadvantage. While tutoring or enrollment in private classes can bridge the testing problem they are not guarantees to more successful college applications, in part because so many people do some kind of test preparation. Indeed, in some communities even those who test well take such courses.

Presumably in your freshmen year of high school you have begun the process of learning what courses are necessary and have taken the courses that you need to apply to specific colleges. If you are thinking of elite colleges or universities (and what is elite is debatable)--or, indeed, any of the flagship campuses of four year state colleges, many of which have select programs for their best students--you should have taken Honors and Advanced Placement courses.

When we think of elite and selective schools we think of such schools as the Ivies, MIT, Caltech, Stanford, Duke, the University of Chicago, Northwestern and many of our great state universities like Berkeley, UCLA, Virginia, Michigan, Indiana, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Texas, along with quite a number of smaller private colleges from Amherst, Williams, Bowdoin, and Middlebury in the Northeast to Reed and the five Claremont colleges out West. But we need to think, too, of such excellent if slightly less prestigious and often less costly universities -especially for state residents--such as (to name a few) Binghamton and Buffalo of the New York State system, the University of Vermont, the University of Oregon, the University of Maryland, and Penn State. (A useful web site is "College Confidential").

In the application process, note that extra-curricular activities and community service matter. But it is better to excel in and/or play a leadership role in one or two activities than to be a participant in a long list.

For non-elite schools, you should investigate the graduation rate and the time from matriculation to commencement.

3) Find a match between the anticipated costs and your ability to pay.Learn what kind of financial aid is available to you and whether that aid takes the form of scholarships, work study jobs, other jobs, or loans. Taking into consideration tuition, room and board, travel costs and allowing some funds for miscellaneous costs, make up budgets for the colleges that interest you.

How much debt you should incur depends on many factors, including your expected future earnings, but be careful about mortgaging your future. In past decades, especially the 1970s and 1980s, because of high inflation students were repaying loans more easily because the dollar they borrowed was worth much more than the dollar they repaid, but this has not been the case for some years. Of course now fixed interest rates are lower than they have been.

How will you pay for college if your parents cannot afford it or are unwilling to pay for most or all of it? The latter problem is sometimes fixed by legally declaring yourself to be an independent adult without supporting family in which cases your aid will be based on your own earnings and assets; be forewarned that this process is not easy. (See "What can you do if your parents refuse to help?").

The good news for those families of modest means is that a sustained effort is being made to help low-income high achievers get the necessary financial support to thrive in college. Whether this effort at economic diversity will succeed depends in part on whether the colleges themselves will sacrifice tuition revenue in the interests of economic diversity. AsDavid Leonardt points out, "On some campuses, including Caltech, Dartmouth, Notre Dame and Washington University in St. Louis, fewer than 15 percent of entering students receive federal Pell grants, which go roughly to students from the bottom two-fifths of the income distribution. One problem is that supporting economic diversity depends on the school's endowment, and those with lower endowments per student have fewer resources.

But more good news is that many of the elite colleges do need-blind admissions and have the resources to help those whom they admit and who need financial assistance. One should not be scared off by "sticker price," because there are means of getting significant support. Also, many schools offer merit scholarships to attract top students. The more highly endowed schools will offer an aid package with a large grant component. Other good news is that the US Department of Education has the Pell Grant program to help fund college education and the maximum 2014-2015 grant is $5730. For the Ivies and other schools with comparatively large endowments, qualification for the Pell is a signal to schools to provide--in almost all cases--generous aid packages. Further good news is there are many other scholarship programs, including those restricted to residents in each state; in New York State these range from $500 to $1500. In addition, there are many private scholarships administered by such organizations as the Rotary, although the latter focuses on study abroad.

Although Cornell does not have the resources of Harvard, Yale or Princeton, in the Cornell class of 2018, consisting of 3261 students, 47.8 percent were eligible for need-based aid and 44.4 percent received need based aid from Cornell sources, averaging $35,735 in grant aid--which does not have to be repaid-- and $5,783 in loans.

Another source of scholarships is athletics, but be aware that neither the Ivies or the (usually) smaller colleges in Division Three offer athletic scholarships. Be aware, too, that many more parents think that their children are candidates for athletic scholarships than there are scholarships and that Division One scholarships often have expectations for practice, conditioning, travel, and competition that take significant time from studies. New rulings seem to allow some schools to give more aid than in the past, but at what price to the student?

In addition, there are various loan programs, although I am wary of loans that saddle young people with enormous debts that can affect their ability to buy a home, start a family, choose a low-paying career such as social work or elementary and secondary school teaching, as well as prepare for retirement. In fact a handful of top universities have eliminated loans from aid packages and I expect more to follow.

Avoid for-profit colleges, many of which have engaged in fraudulent practices and are responsible for a disproportionate amount of student loan defaults. Several government studies have exposed these schools as taking advantage of gullible students and making exaggerated claims.

4) One key to college success is finding professors who are interested in you; it is worth researching whether teaching and mentoring are stressed at the colleges to which you apply.

Before you decide where to apply, the more you can learn about the school and the departments and professors that interest you, the better.

Both small colleges and large universities have great teachers, but the latter will have more courses taught and graded by graduate students who may also serve in the sciences as lab instructors. On the other hand, research universities will offer a wider variety of courses and programs.

Is it better, you might ask, to work with a world-class scholar at a top research university who opens the doors to exciting and complex projects and ideas than with a capable, enthusiastic professor who does little or no research? Or are you more likely to find at an excellent small college a professor who challenges you and shows interest in your growth as a person?

There is no one answer, but in my experience you are just as likely to find the ideal mentor at a large

university as at a small college. Katherine Burroughs, Cornell '85 recalls: "What is really remarkable though

is notwithstanding the size of [Cornell}and the focus on being a research institution, I can count on a few

fingers the bad experiences."

Keep in mind that major research universities can offer students opportunities to work with senior scholars on

grants and give you a leg up for graduate school. There are programs like Cornell's Presidential Research

Scholars that enable student to do independent research under the auspices of a senior scholar; these programs

are not limited to the sciences but can include the humanities.

My sense is that teaching at research universities, including teaching in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) courses, has improved gradually and dramatically in recent decades. At research universities, teaching effectiveness is not only more a component in tenure decisions but is also stressed more in the administration's review of a department's and individual performances than used to be the case. But certainly at some universities teaching should be stressed in some disciplines more than it is.

Because of a tight job market, professors trained at the strongest graduate programs are everywhere now, and

you will be able to find excellent mentors not only at the most selective colleges and flagship state

universities, but at almost any college, including community colleges.

5) Suggestions #1-#4 means that you need to do the necessary research.This means finding the

tine to do some reading in catalogues and online sites--and, if possible speaking to people attending the

colleges that interest you. Talk not only to your guidance counselor or the person handling college

applications, but also to teachers whom you respect.

6) Visiting colleges is a good idea but don't overestimate what you learn in a campus visit.The best visits are overnight ones during the week that include living in the dorms and visiting classes rather than visits on football weekends at schools where football is foregrounded.

If you are a prospective athlete you will meet the coach and if he or she is interested in you as a potential player, you may be recruited with tales of championships and even exposed to campus partying, especially on weekends. You need to look at athletic facilities, find out how likely you are to play, and if you are offered an athletic scholarship, find out whether you lose that if you are injured or if you or the university decides you are not going to be on the team You need to do some research into whether the school is using you to bolster its athletic reputation or if it is really interested in your getting an education. There has been ample evidence that some schools universities are not educating many of its top athletes, especially in visible and revenue earning sports.

The worst reason to go to any college is because you think there will be lots of partying and sometimes eighteen year olds forget this.

7) Early decision (which is binding if the college accepts you and usually requires an application in November) and early action (which does not require a commitment until the regular commitment deadline of May 1) are often good options and in many elite schools give you a better chance of being admitted.For either, you apply to only one school. Early action still gives you a chance to apply elsewhere and compare financial aid offers. However, if you do early decision, you cannot compare financial aid packages; for those needing aid, early decision may not be the best alternative.

In my limited experience on admission committees at Cornell's College of Arts and Sciences those deferred during the process of admitting early decision applicants do not usually get admitted later. Nor are many students admitted from the so-called wait list. My guess is that this is true at virtually all the select schools and if you are deferred or waitlisted, you need to find out the facts on these matters. Your slim chances of being admitted off the wait list are increased by writing an enthusiastic letter expressing your strong interest, but don't become a nuisance by frequent writing and calling.

8) For those taking part in the regular application process or those who are rejected or deferred in the early decision or early action process, "safety schools"--those whom research plus your guidance counselor find are likely to admit you-- are a good way to avoid disappointment.

9) Think of the college admission process as an Olympic event in which you do your best, but if you don't get admitted where you want to be, be a good sport and realize this is NOT a judgment on your life to date or your potential.What you do at college is far more important than where you do it.

10) Once you have made a choice, commit yourself fully to that choice rather than thinking about "would haves" and "should haves" or what might have been.

11) Transferring is a possibility--and some schools give students "guaranteed transfer" if they meet certain stipulations--but in most cases the best thing is to give your all at the school in which you enroll.

If you are doubtful about which field you want to go into, choose a larger university with many choices of fields in which to major. That choice may be more important in STEM because you are preparing for a specific career than it is in the liberal arts where your skills in reading, writing, thinking analytically, making oral presentations, and summoning evidence are most important; in some liberal arts fields, you can move readily from one area to another. (See my "Why Study the Arts and the Humanities)."

In general it is easier to transfer from science and engineering programs into liberal arts than vice versa. Put another way, if you are interested in STEM, it is best to start in STEM.

12) One way to save on costs is to apply to a Canadian University or a university abroad.Canadian universities often do not require standard test scores or recommendations or essays--and some only require senior grades-- but they do give preference to students in their province. Canadian students submit their application to an application service or to the university and list their preference order. (See "10 Reasons to Attend Canadian Universities").

At Queen's University, one of Canada's elite schools, an American student's costs for tuition plus room and board might be in the neighborhood of two-thirds of an elite American school. Not only are there merit scholarships for international students, but you can also still apply for loans offered by the US government under theStafford ProgramandPLUSloan programs.

Universities in countries other than Canada are also possible choices and will be less costly than the most expensive US universities (See: "The Complete University Guide").

British Universitiesrequire the Universities and College Admission Service

Application.

Only Oxford and Cambridge require applicant interviews; both welcome but do not require SAT and ACT test

scores. For Oxford and Cambridge, an essay is also required but it is, rather than a personal essay, one

focusing on your academic plans.

Alternative Paths to a College Education

But there are many other scenarios other than the college Olympics. Great teaching and mentoring can take place at Community Colleges and commuting four-year schools. When cost is an issue or when you are undecided on your direction, commuting to college can make a great deal of sense, and so can spending your first two college years getting an associate degree at a Community College.

Some states have innovative programs for getting a college degree. For example, New York's Empire State College has a fully accredited program for associate and bachelor degrees which allows a combination of online and on site courses and even gives college credit for certain kinds of work experience.

Questions that are part of the process for many young people:

Is college for everyone? Do you want to go to college upon high school graduation or would it be better to go into the Armed Service and go to college later when the Service will pay much of the costs? (See, for example, "US Army Benefits"). What if you have had to work for some years to support a family? What if, because of financial reasons, you are thinking of going to college part-time? What if you didn't do so well in high school, but now, after working or military experience, you feel ready for college? What if you need, for family and personal reasons, to stay home?

For some students, the answers to the foregoing questions will lead to a decision to begin your higher education at community colleges. Despite the focus in my earlier comments on "elite" and "selective" colleges, we need to remember almost half of US undergraduates are enrolled in community colleges and many more are in four-year commuter colleges where the road from high school matriculation to graduation can be difficult.

In "Community College Students Face a Very Long Road to Graduation," part of a series focusing on LaGuardia Community College in Queens, New York City, Gina Bellafonte writes:

In recent years, mounting concerns about inequality have fixated on the need for greater economic diversity at elite colleges, but the interest has tended to obscure the fact that the vast majority of high school students -- including the wealthiest -- will never go to Stanford or the University of Chicago or Yale. Even if each of U.S. News and World Report's 25 top-ranked universities committed to turning over all of its spots to poor students, the effort would serve fewer than 218,000 of them. Community colleges have 7.7 million students enrolled, 45 percent of all undergraduates in the country. . . .

More than 70 percent of LaGuardia students come from families with incomes of less than $25,000 a year. The college reports that 70 percent of its full-time students who graduated after six years transferred to four-year colleges, compared with just 18 percent nationally, but only a quarter of LaGuardia students received an associate degree within six years.

Students at community college at times do not have access to the mentors and counselors who understand the ins and outs of transferring to four-year schools. If you take this route, you need to educate yourself on these matters and, in the best case, find mentors among your teachers and advising deans who will help you.

My former Cornell English Department colleague, Phillip Marcus, now teaching at a less selective four year college, Florida International, eloquently reminds me that there is world quite different from Cornell and other prestige schools, a world in which professors face challenges that Ivy League and other elite schools can hardly imagine:

To give another perspective that shows how difficult success at college can be for those marginally prepared, I cite Wendy Yoder, Retention Coordinator at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, another non-elite four year university:My own experience for the past twenty years would be quite different from yours as 80% of our 60,000 students are minorities (Hispanic, African-American, Afro-Caribbean) and most of them come from poor families and almost all work part time or even full time while carrying full loads of classes. I always have students who can't afford the textbooks. . . .

My students here face so many daunting challenges just to afford to go, though our cost is about 50 K lower per year than [Cornell]. . . As an example of differences between CU and FIU, the state mandates that we submit textbook orders very early, because a great number of our students simply cannot afford to buy new books and must search for used ones. Often the bargain books don't arrive in time and students are without books during the first crucial weeks of the semester.

Southwestern is . . . dedicated to students and willing to implement whatever changes necessary to optimize the success of our students. . . [W]e sometimes overlook the natural waning process that occurs between a freshman and senior class. College is not for everyone, but I believe that we can make a positive influence in the lives of our students even if they decide on another path in the future.

Despite these difficulties, four year schools like Florida International and Southwestern Oklahoma, where many and in some places most students are commuters, provide a viable alternative to the more expensive colleges and offer students without great means and perhaps honor grades in high school a chance to earn the necessary college degree to find a good job and make a difference in their communities. Similarly, community colleges play a crucial role for a great many students. They are often feeder schools for state university systems and provide a resource for upward mobility. They offer associate degrees after two years of successful full-time study. But because many of their students work full time and go to school part time, progress can be slow and many students drop out of classes during the term. Yet many students thrive in these schools and go on to graduate school.

Conclusion:

While not for everyone, higher education will not only expand your earning power by developing your

skills and intellect, but also open the doors and windows to the pleasures of reading and the joy of

learning.

“The College Olympics: How to Choose the Right College and How to Get the Right College to Choose You,” Huffington Post, Nov.11, 2014, http://t.co/Bx3506gqWR

17 Suggestions for Choosing Classes in College

After making suggestions to students about how to negotiate thefreshman year, sophomore year, junior year, and senior year, I have been urged to write a piece on how to choose classes. My suggestions, in no particular order, follow.

1) Even while filling pre-requisites and requirements for your major as well as distribution requirements during your first first two years, each term -- if time permits -- take one class that expands your interests.In some cases, required distribution courses will be expanding your range of interests.

2) After you choose a major, continue to take one course a term that expands your interests or develops necessary skills that complement your major.Even after fulfilling basic graduation requirements, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) majors need to expose themselves to the humanities and social sciences; humanities majors need to take some basic sciences and social sciences; and students in the social sciences need to think about the humanities and science.

No matter what your major may be, you will need to develop tech skills. Every student needs to have a course in computer science and in economics, and every student needs to learn how to write lucidly and precisely and to learn to use evidence to make a well-structured argument. Take as many courses as possible that require extended written assignments.

Matt Barsamian, Cornell '04, observes: "I strongly agree with your admonition that students should step outside their comfort zone. I believe I dropped Introduction to Microeconomics three times as an undergraduate and never wound up taking it. I still regret not doing so. College is a rare opportunity where you can learn about just about anything and it is very very difficult to find the time and motivation to do so once you are working."

3) During your four years in college, take classes that cultivate new interests.Try a class or two in creative writing, music, art, and/or theatre. A basic survey course in these fields will give you an overview. Such classes will be an investment because they will prepare you for a lifetime of enjoyment.

In the humanities, where pre-requisites are less important, a more specialized class may be more challenging and ultimately have a higher yield in terms of introduction to a field. Thus what you learn from an in-depth class on Mozart will carry over into your understanding of Beethoven or Brahms, and what you learn about seventeenth century Dutch painting will help you understand the Italian Renaissance.

If you are not a scientist, take a class or two that enables you to understand such social and political issues as climate change, epidemics, population growth, genetic engineering and testing, and fossil fuels. At the very least you will be an informed citizen, but you may also have a chance in the future to shape policy on some of these issues within your community.

4) Speaking to other students about a professor or classes is a valuable source of information, but it is important to know how serious and responsible your sources are.Keep in mind that the best teachers offer courses that are often demanding. If you know that such a splendid class outside your major must get less of your attention in terms of effort and commitment, you might take it using the Pass/Fail option rather than miss the learning experience.

5) Sign up each term for as many courses as your school will allow and go to more classes the first week than you plan to take.After a few classes, you will have a good idea whether the class is for you. In addition, if need be, you can just go to larger classes without signing up. But where enrollment is limited, it is best to have your name on the initial list.

6) On the whole, when possible, take professors, not courses.Taking classes with engaged professors who love their subject and communicate their passion and in-depth understanding is part of the joy of learning. Such professors can brighten an entire semester as well as the entire college experience.

7) Find professors who are interested in their students and care about their students' growth.It may be reductive to say that some professors teach their subject, others teach their subject to individual students, but there is a good deal of truth in that distinction.

The professors who ask you about your plan of study, your goals, your outside activities, and seem to care about you as a human being will not only be those you can go to for advice, but those who could be a future reference. And thinking about who will be future references is important.

8) Remember, too, that no professor is the best professor for everyone.But in general, the best professors are those who expect you to come to every class prepared, take attendance, have high expectations, and give challenging assignments. The best professors not only treat student assignments carefully and expeditiously but also prepare each student to do the assignments successfully,

9) Take classes that emphasize concepts and how to apply them.Learning by rote is less important than learning how to think for yourself and to solve problems, a crucial quality for your future. Of course, some classes, like those in basic foreign language, do emphasize developing basic skills.

Learning how to think is a quality that develops in part from watching professors work through issues and synthesize on their feet when answering complex questions as well as understanding how they conceptualize assignments and exam questions. Most importantly, learning how to think involves solving problems and meeting challenges connected with papers and exams and, in STEM courses, complex conceptual and theoretical issues as well as interpreting the evidence from experiments.

Be aware that some problems are intractable and vague and courses that put everything in PowerPoint and neat packages are at times suspect. In your future career as a doctor, lawyer, government employee, or researcher, you will come upon problems that cannot be neatly solved or solved at all.

10) A current buzzword is "metacognition."What that means is knowing about knowing, or knowledge about when and how to use particular strategies for learning or for problem solving. Thus, when writing a paper or pursuing a lab experiment or social science project, think about what you know, what you need to know, what you can't know and how to use that mix to solve intellectually challenging problems and paradoxes.

11) Take courses that stress integrative learning, that enable you to understand material beyond one course, and to transfer what you have learned in one area to another area.

If your course in Russian literature enables you to better understand Putin's aspirations and follies, you would be integrating your learning. Another example is reading di Lampedusa's masterwork, The Leopard, not only for its literary value but to better understand Italian and Sicilian history, politics, and class divisions as well as continuing economic tensions between Northern and Southern Italy. Using psychology, including psychoanalyses, to understand literary characters and their authors is another example of integrative learning. By combining science and economics, integrative learning can also help us understand the effects of climate change on future generations.

12) Take courses where the professor can put material in context, reference other fields, and has some knowledge of the world beyond the classroom.Reading the New York Times in print or on the internet is one way for you to keep up with the world at large, including environmental and sustainability issues that affect us all, as well as how our government functions and how we can change it.

Follow international news and have a map of the world or a globe in your room and relate what you learn and read to specific places.

13) Take courses that help make you aware of ethical and moral issues.You are preparing yourself for life and such awareness will not only make you a better citizen, family member, and employee but a better member of the campus community.

14) Learn to think about the experiential implications of what you are learning and how solving academic problems can carry over into other aspects of life.Conversely, find internships and campus activities that give you an experiential base for what you are learning. Depending on your field, this could take the form of working in a lab, as a museum guide (docent), for a university publication or on the campus newspaper. Find summer internships and positions that enable you to integrate your knowledge with your experience.

15) Supplement the classes in which you are enrolled with lectures by guest speakers, audits, and occasion visit to classes that you are hear are stimulating.A professor will generally welcome guests.

16) Take courses that require your participation.At best such courses become communities of inquiry, and communities require working together. Learning how to be part of a functioning group comes from small classes requiring participation.

In your career, you will need to work with people, and employers like people who can work in collaborative situations, who know the basics of teamwork, and who respond to the ideas of others even while sharing their own ideas.

17) Because of the Internet, we live in a global village with virtually instant availability of news (as well as social gossip) as events occur and develop.While we cannot know what future technology will bring us, we do know that students need to take courses to prepare for continuing internationalization. Language skills are important, even if English has become he educated world's lingua franca, that is, its common language. If you want to be part of globalization -- and you have no choice -- you might think about learning Chinese while in college, and if your focus will be the Americas, fluency in Spanish is necessary. Collaboration in research and business and social programs can depend on language fluency.

Conclusion

Discussion-oriented classes in which you learn to articulate your perspective and respond to that of others are valuable not only for clarifying and refining your thinking, but also for developing essential tools for participating as a valued team member at work, in your avocations, and in the civic life of your community. Indeed, the give and take of ideas is what separates democracy from other forms of government.

"17 Suggestions for Choosing Classes in College,"”Huffington Post, May 5, 2015,http://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-r-schwarz/seventeen-suggestions-on_b_6807322.html

Twenty Suggestions for Incoming College Freshmen

With millions of college students about to begin their freshman year within a few weeks, it is an appropriate time for entering students to think about how to succeed in college and, in particular how get a good start in what is a life-changing experience and opportunity.

In 2012, I first published my "Suggestions for Incoming Freshmen" in theHuffington Post. Taking account of comments from readers and students, I have published updated versions each succeeding year. I have also written quite a few other Huffington pieces onhigher education. My forthcoming book on undergraduate education for Wiley-Blackwell, entitled How to Succeed in College and Beyond: The Art of Learning, is now in press.

My primary credential is that I have been a Cornell English Professor for 47 years and have also held visiting professorships at various public universities in three other states.

The following suggestions apply to all entering freshmen, although a few may be more apropos to those living on campus. Needless to say, this is far from an exhaustive list, but one that students, parents, and colleagues might think of as a point of departure.

Basics

1) Keep your career and life goals in mind, and remember why you enrolled at the college and in the program you chose.

2) College is an opportunity, but you need to be a savvy consumer, and that means much more than not wasting your own money or that of your parents and not running up loans beyond you and your parents' ability to repay.

Being a savvy consumer means taking advantage of what is offered in terms of personal and intellectual growth as well as developing the necessary skills for the next stage of one's life.Savvy college consumers take advantage of opportunities and learn what resources are available, not only on campus in terms of courses, professors, extra-curricular activities, museums, theater, work, and volunteerism, but also within the community in which the campus is located.

3) After a reasonable amount of time, if you and your academic program are not a good match, think about changing direction within the college or, if you are at a university, transferring to another college within that university.A "reasonable amount of time" is admittedly vague; when to change direction will vary from person to person. Student input has made me think that in most cases at least an entire academic year is more appropriate than one semester.

Yoshi Toyoda, Cornell'14, counsels that students should be patient before changing fields:

For many science/math/engineering majors, a lot of freshman and sophomore classes are going to be laying foundations that may not be obviously related to your field. For example, all of my engineering friends had to first get through all of the differential equations and physics courses which they may not have enjoyed in order to fulfill the prerequisite to take upper-level, interesting, applied engineering courses.

One should take one's time about transferring to another college or university unless it was always your first choice and you had been given "guaranteed transfer" if you met certain stipulations. Be sure you are not transferring just because you are being asked to meet higher standards than in high school or that you are not the center of attention that you were in high school.

Subin Chung, Cornell '15 and a transfer, advises:

[A] student should probably take at least a year (rather than a semester) to judge whether t they should transfer - one semester isn't enough. First semester is often just adjusting to change; second is when you really realize whether that particular school is the right fit for you. I find that many of my transfer friends (and myself included) tend to think so.

Time Management

4) If any one thing determines success in school and in life for people of comparable potential and ability, it is time management, that is, using time effectively and efficiently.Keep a daily record of how you are using your time; each evening, schedule the next day, even while knowing you won't be following that schedule exactly.

You need a regular routine for doing your academic work. When you are awake, think about how the day will be going in terms of time, including how much time you will be spending on extra-curricula activities (varsity or club or intramural sports, university publications such as the school newspaper or literary magazine, band or orchestra), paid employment, community volunteering, and social activities.

Jenni Higgs, Cornell '01, suggests:

[I]t might be helpful to encourage students to explore resources on campus that can help them adjust to new academic demands (e.g., study groups, counseling/study centers, etc.) It might be comforting to freshmen to know that it's common to feel overwhelmed initially and that there are plenty of organizations on campus to help them through rough patches.

An important Basic Rule: no time period is too short to accomplish something, and sometimes--especially when writing about something that you have been thinking about for a while--the time constraints of 15 or 20 minutes can actually produce better results than longer time periods. It may be that in some cases if people have less time for a task, they are moreefficient.

If you have time between classes, learn to use that time. If you have a fifty-minute class at 9:05 that ends at 9:55 and another that begins at 11:15, use those 80 minutes productively.

Know that the week has 168 hours. Be aware of how much time you spend with your smart phone, email, and social media such as Facebook, Twitter, etc. Be aware, too, of how much time you spend on social activities.

In July 1718,Cotton Matheradvised his son Samuel, as he was going off to college:

My Dear Child, look on Idleness as no better than wickedness. Begin betimes to set a value upon time, very loathe to throw it away on impertinencies. You have but a little time to live; but by the truest wisdom from you may live much in a little time; every night think how have I spent my time today, and be grieved if you can't say, you have gotten or done some good in the day.

Mark Eisner, Cornell Ph.D. '70 who has been both a teacher and administrator at Cornell, and has also spent time in private industry, admonishes:

In managing time, it is important to be aware, not just of a schedule, but of how productive you are able to be at each point in the schedule. All hours spent on tasks are not equivalent - if you are overtired it can take extra time to complete tasks, and if you miss a class or fall asleep during [the class], it can cost more time to catch up than it would have taken to be in class and attentive to the material. That extra time then gets stolen from other tasks, with the risk of falling further and further behind.

Zivah Perel, Cornell '99, who teaches at Queensborough Community College, CUNY (The City University of New York), reminds us of the differences between students at elite schools and urban students balancing college with other demands: "My students have a hard time balancing the demands of their jobs, the demands of their families, and school. It's hard to know what to tell them, since I understand when they sometimes (or even often) have to prioritize something other than my class." Adding an eloquent personal note, she writes: "It's interesting coming from a place like Cornell, which was a totally different type of institution than where I am now (obviously). I so valued my time at Cornell and had always hoped to teach some place like it, but I find my work now so rewarding and important. These are students who need good teaching and someone who values them academically. So often that hasn't been the case for them."

5) Come to every class on time, alert, prepared, and ready to take notes.

In response to the above sentence, Peter Fortunato, Cornell '72, a former student of mine who taught as a

lecturer at Ithaca College for years and in the Cornell Summer College, wrote: "Learn how to take notes (most

students, I've found, really don't know how to do this, or nowadays expect teachers to supply power-point

notes!) and how to connect writing and thinking whatever the subject matter."

Work on your courses every day but not all day; do something that is fun and relaxing every day, whether it be

formal activity like participation in an intramural sports or a singing group or a walk in the woods, a visit

to a museum on or off campus, or a pick-up basketball game.

Fortunato observes: "Learn how to relax and focus, either by taking a stress-busting workshop or meditation class or guided relaxation class. Students do much better in college when they are intentional about these matters or have teachers who add such activities to class time."

Participating in Campus Life

6) Experience complements what you learn in classes.Try to find summer jobs, campus jobs, and campus or community activities that parallel your goals. If you need or want a part-time job, try to get one compatible with your goals as a way to test whether you are on the right path. But also use jobs and activities to expand your horizons and interests.

Yet if financially possible, during term keep most of your time for academic work with some left over for extra-curricular activities and community volunteering.

In general if you are at an elite college or university, ten or twelve hours on a paid job is enough. To be sure, at less demanding colleges and universities, many students--particularly older students, some of whom have families to support or help support-- carry a full course load and work much more at jobs.

Gabrielle McIntire, Cornell Ph.D. '02 and a professor of English at Queens University in Canada advises:

Prepare to work hard: this is the gateway and ticket to your whole future, and it is worth investing everything you have in this four-year period to keep those gates wide open so that you have as many choices as you possibly can upon graduation. I remember somehow figuring out in undergrad that it was well worth my time to have a minimal part-time job (5 hours/week), and to use my "extra" time on pushing myself as hard as I could scholastically since that was the REAL investment in my future. That is, instead of earning $10/hour doing more part-time work, and thus having a bit more cash at hand in the moment, I realized that it would be better to be slightly poorer during undergrad which would then allow me to have many more rewards after [undergraduate years].

7) Be sure to participate in one or more of the many campus activities, but during the first term choose a limited number until you are confident you can handle your course workload.

8) Given that this is a tech-driven world, no matter what your major, develop tech skills, perhaps by taking basic courses in computer science if you have not already done so in high school.If you have done so, consider taking another one in college. Virtually every student who didn't developed tech skills has expressed regret to me.

Ryan Larkin, Cornell '14 advises: "Learning how to code (even basic HTML and CSS) would have been an invaluable step for me to take in high school, and some of the first advice I'd give to students would be to acquire hard technical skills that can add value to almost any kind of resume."

Kyle Sullivan observes:"[T]he world is developing at such a rapid pace and having the hard technical skills is almost a must in most job situations that aren't sales related. Although I'm in a sales position right now as a Small Business Commercial Lender for M&T Bank in New Jersey, I recently taught myself the basics of HTML CSS, and Java through a website called codeacademy.com because that's something that won't change and will be quite valuable just for personal use moving forward."

Broadening Horizons and Expanding Interests

9) Take advantage of lectures outside the areas of your course work as well as special exhibits, campus theater presentations, musical and dance programs and other campus resources as well as the natural and/or urban treasures and cultural resources of the area in which your college is located.

10) The world has become a global village. For you to be part of the village, you need to spend some

time each day keeping informed about international and national news.That means reading a major

newspaper in print or on the Internet like the New York Times.

Reflecting on conversations he had with fellow students, notably during the financial crises but also on other

occasions, Kyle Sullivan, Cornell '11, notes:

Some of my most valuable lessons in college came from the discourse I had with friends, friends from different upbringings and experiences that reflected their background and the places they came from or even visited for a brief or extended amount of time. Just having that intelligent and thoughtful discourse with them changed the way I look[ed] at a problem, or a topic and changed the way I react[ed] to [it]. . . . I remember sitting in the fraternity house huddled around either CNN or MSNBC and switching to Fox News to get a different perspective and learning so much just from listening to the conversations being had from the other guys sitting around the TV.

Choosing Classes and Studying

11) Think about your classes as communities of inquiry where you, your fellow students, and the professor are sharing intellectual curiosity, love of learning, and the desire to understand important subjects.I concur with what I have heard over the years: "If so-so [recognized at Cornell as a truly great professor] is teaching the Manhattan phone book, take it. "

Rachel (Greenguss) Schultz, Cornell, '83 emphasizes:

It is important to take interesting classes with great professors. Find out who the good teachers are and take their classes. Of course you need to be interested in the subject but sometimes a great teacher can awaken a passion.

I also think it is less about taking courses that fit your career path and more about taking classes that teach you how to think and learn. Success in adult life depends so much on being a life-long learner and any tools you glean in college to hone this skill will set you up for success later in life.

Take classes that emphasize concepts and how to apply them. Learning by rote is much less important than learning how to think for yourself and to solve problems; the latter skills are crucial for your future. Be aware in your thinking of what you know, what you need to know, and what is unknowable.

But the right class for you may not be the right class for others. Emily Choi, Cornell '14, counsels, "I think it's always good to register for as many classes as you can, and to go in your first week, even if it's just to feel them out." If possible when a class or professor is not fulfilling your expectations, drop it or change sections.

Some students, especially in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) enjoy study groups. As Zhongming Chen Cornell ' 14 recalls:

I felt that studying with friends was a key to my success. I . . .made a lot of close friends this way It was a great way for me to bridge my major activities (academics, social life, and athletics) too. I understand that I may be a little biased though. I did head teams that created videos for the Learning Strategies Center that promoted these methods. I was that passionate about it! Also, this method may not be equally applicable to all majors (the videos my teams prepared were for the biology and chemistry departments).

In small classes, participate in discussion and ask for clarification; in large ones, don't hesitate to ask questions if you have them and to visit the teaching assistant or lecturer's office when you need help.

Peter Fortunato suggests: "Learn how you learn; that is, whether you are primarily an information-based (facts and figures), visual, auditory, 'hands-on,' or interpersonal (teamwork) based learner. Many professors and curricula assume that all students function in the same way in their respective courses."

Eisner notes: "There is more to learning something than absorbing facts and techniques. Try to find opportunities to explain the subject matter to someone else, or to write an explanation in your own words. The best learning is active learning."

12) Get to know at least one professor reasonably well each term.The professors who ask you about your plan of study, your goals, and your outside activities, and seem to care about you as a human being will be not only resources that you can go to for advice, but also potential future references. If one or more professors become your mentors, mature, stable, selfless people for whom your personal and intellectual growth and future success in whatever you choose matter, you will be most fortunate. Although students are just as likely to find valuable mentors at large colleges as small ones, they may need to make more effort to reach out, and connect with professors. Even within the same college and university, department cultures are not the same. Where teaching is valued and teachers spend time with students, you are more likely to find a mentor.

Once you arrive at your school, I suggest visiting professors during office hours, showing interest in the subject (taking the initiative to do extra reading and then asking the professor about it), participating often and thoughtfully in class, as well as attending optional learning activities. All of the aforementioned are ways to find a mentor at a college of any size.

For Becca Harrison, Cornell '14, finding a mentor was crucial:

In high school, no one would have cared if I fell through the cracks; at Cornell (and probably many institutions), the minute I reached out to my chemistry professor and graduate student Freshman Writing Seminar instructor for help, I realized that finding a mentor who truly cared about my success made it possible to learn how to learn and work effectively.

Matt Barsamian, Cornell '04, advises:

You discuss, in the tips for incoming freshmen, getting to know at least one professor well. I think that is invaluable. I was fortunate enough to get to know three or four professors/instructors fairly well. I would also emphasize the value of attending office hours and point out that they don't exist merely for those students who perceive themselves to be struggling to understand the material or in response to a bad grade on an exam or paper. I would highly recommend visiting every professor at least once during the semester during his/her office hours as an opportunity to connect. I think it also evidences a student's interest in and commitment to the course.

By knowing some of your professors, you will not only feel more a part of your college community, but you will also have necessary references for programs within college, work positions, and graduate school.

In "It Takes a Mentor,"New York TimescolumnistTom Friedmanhas written:

What are the things that happen at a college or technical school that, more than anything else, produce "engaged" employees on a fulfilling career track? According to Brandon Busteed, the executive director of Gallup's education division, two things stand out. Successful students had one or more teachers who were mentors and took a real interest in their aspirations, and they had an internship related to what they were learning in school.

13) Find a few comfortable and quiet study places on campus, places where you work effectively and are not easily distracted.If you are commuting, you will still need to find places where you can focus on your academic work.

Maintaining Physical and Mental Health

14) Participate in campus activities--teams, musical and dance groups, community activities that serve the underserved and aged--and attend seminars that call upon collaborative action.Such collective endeavors give you an opportunity to develop group responsibilities, including social ethics and leadership skills necessary for later life. (I am skeptical about the need for fraternities and sororities in 2014, a subject I will discuss later, but they do respond to the social needs of many students.)

Students who participate in campus activities get more out of their college experience and feel more satisfied with their college years both while at college and when looking back from a distance of years. Richard J. Light notes that, based on surveys, "a substantial commitment to one or two activities other than coursework--for as much as twenty hours a week---has little or no relationship to grades. But such commitments do have a strong relationship to overall satisfaction with college life. More involvement is strongly correlated with higher satisfaction" (Making The Most of College: Students Speak Their Minds, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2001, 26).

15) Remember the three R's: Resilience (Falling down and getting up are one motion.); Resourcefulness

(Use your skills and intelligence.); and

Resolve (Pursue goals with determination and persistence.)More likely than in high school, you are

going to have disappointments and frustrations, but overcoming them is part of the process of preparing for

the world beyond college.

In between completing her freshman year and beginning her sophomore year, Pauline Shongov, Cornell '17, observed: "[F]reshmen should never underestimate their talents but also should be humble in everything they do. If they strike a balance between these two, they will be open to everything college life has to offer and will thus win others' respect while maintaining self-respect in return."

16) Look at setbacks and problems as challenges to be met and overcome; when you do so successfully, you will be gaining confidence to meet the next challenges.

Learning to build on failures is an important quality for success, as many of my former students attest.

Becca Harrison, Cornell '14, recalls "the value [for her] in failing, and not necessarily succeeding right out of the starting-gate that is freshman year." Recognize that all problems--personal and intellectual--are not neatly solved, and learn how to deal with complex and ambiguous questions.

Alyson Favilla, Cornell '16, adds:

The only thing I might suggest is adding something [about] adjusting personal expectations for success. Number 16 on the list [about handling setbacks and problems} was great, but requires significant perspective that isn't going to be available to students currently struggling with something that feels far out of their depth. Many students, especially those from highly competitive, privileged areas, have never before had to confront the limitations of their own abilities. Recognizing those limits, and determining to improve on them, I think, is an important lesson; knowing that you can successfully apply yourself to difficult or new material is very different than expecting to understand it right away, or feeling disheartened when you do not. Similarly, success does not always engender satisfaction. Being good at something, or achieving conventional academic success at that thing is not always a reason to pursue it. For me, that was an important thing to consider when deciding whether or not to switch programs.

17) When you enter a new situation such as the first weeks at college, you might feel somewhat desperate to make friends quickly.But it is important to retain your core values and judgment and to avoid becoming part of a herd or doing things only because others are doing them.

Quoting Psalm 139,Cotton Matheradvised his son going off to college: "[H]e that walketh with the Wise, shall be wise, but a companion of fools shall be destroyed. Shun the company of all profane and vicious persons, as you would the pestilence."

The period between entering school and Thanksgiving is sometimes known as the "Red Zone" because students are more prone to make bad choices, whether they be partaking excessively of substances that suspend their judgment or putting up with physically abusive hazing or bullying roommates. It is no disgrace to change roommates or to move to a different floor or dorm. If you feel a situation is beginning to get out of control, do not be afraid to protest to campus authorities, or, if you feel the situation is dire, to call psychiatric services or the campus police.

Seek help when you need it, no matter what the issue.

Mark Eisner, Cornell Ph.D. '70, succinctly observes: "There is no shame in seeking help, and doing so can save your education and possibly even your life."

18) Take Care of yourself physically and emotionally.Be sure to get enough exercise and

sleep, and be sure to eat regular nutritious meals. Sleep deprivation can lead to poor performance and poor

judgment.

Eisner, Cornell Ph.D. '70, puts it well:

19) Know that substance abuse is a problem on campuses, with alcohol being the most abused, and that use of alcohol and illegal drugs can lead to compromising situations in which judgment is skewed.Sometimes you have to sacrifice what you could have learned through an all-nighter in order to get to bed at an hour that ensures a productive day the next day. Preferably you should set a regular bedtime and get to bed at that time each night. If there is not time to do everything, consider productivity in choosing which tasks to short change and when to sacrifice them. Studying course material (and thinking deeply about it) as you go along is more efficient than cramming at the end.

Brad Berger, a father of a Dartmouth student and a reader of myHuffington Postarticles, feels that colleges abnegate their responsibility in not enforcing laws that forbid under age drinking:

When colleges allow drinking on the campuses, they are saying students and colleges can pick and choose what laws to break. Not only are they disregarding the drinking laws but also the behavior caused by the drinking is dangerous and destructive. Underage drinking in my opinion is the issue most important to colleges and least talked about.

20) Laugh a lot and continue to develop your sense of humor.When things are not going well, remember you can't fix the past, but you can start where you are and create the future.

“Twenty Suggestions for Incoming College Freshmen,”Huffington Post, July 22, 2015,http://www.huffingtonpost.com/daniel-r-schwarz/twenty-suggestions-for-in_b_7859008.html

Nineteen Suggestions for College Sophomores

After publishing articles in Huffington entitled “Suggestions for Seniors Graduating College” and “Fourteen Suggestions for Incoming College Freshmen” as well as “What to Do with a B.A. in English?” and “Why Study the Arts and the Humanities?” I have been asked if I had any suggestions for the years at college and in particular for the sophomore year.

Speaking to Cornell audiences about my suggestions for seniors and talking to my own students, I began to realize that students need to focus on planning at a much earlier stage than their senior year. Colleges and universities are becoming increasingly proactive about providing resources to help your planning. For example, the Cornell College of Arts and Sciences now has an Assistant Dean & Director of Career Services. So drawing upon my 46 years as a professor since arriving in 1968 at Cornell, and realizing that others will have additional suggestions, here I go with nineteen suggestions for sophomores who more often than not are nineteen years old. I would foreground my first three suggestions but after that there is no order.

1) Sophomore year is a time to think about the future-whether it be employment or further education or a combination of both. With the future in mind, you should choose your college major, your summer employment and internships, your community service, and at least some of your extra-curricula activities. Think about preparing yourself for graduate school-medical, law, masters or Ph.D.-and find out what the requirements are. Many MBA programs prefer some years of work before graduate school.

Develop your character in terms of self-knowledge, integrity, leadership, compassion, and judgment. Who you are becoming is as important as what skills you are developing.