A / V

|

* * * * *

Reads several poems live during a 30-minute radio interview

* * * * *

Reads "Tesla on a leash", June 6, 2008 at Tsegyalgar in Conway,

MA during a retreat by Choegyal Namkhai Norbu.

* * * * *

Mary Gilliland reads ‘Apples,’

from the book Like

a Fragile Index of the World, a special poetry collection

celebrating the inauguration of David Skorton as Cornell's 12th president.

Sep 5, 2006, 1:00 PM.

Listen and see Mary read her poetry.

* * * * *

Poetry (2000)

commentary on ‘Quarantine in the Borders’ – Mary Gilliland

Lucky me—a month at Hawthornden Castle International Retreat for Writers in 1995. Situated on the brink of the River Esk, on a ravine twice as deep as the gorges of New York’s Finger Lakes region where I live, the castle grounds give the impression of wildness even though it’s located just 7 miles south of Edinburgh. In Scotland my feet found a homeland. It’s the first place I’ve inhabited where nobody asks how to spell Gilliland. And I got to sit quietly across the river in Rosslyn Chapel as often as I wished, before the chapel was remade with placards pointing out the Green Man etcetera and a tea room for the busloads of tourists that stop there now. I wanted to visit the Roslin Institute for a peek at Dolly, the first cloned sheep, but access was denied. It seemed a wonder to me that two buildings a stone’s throw from each other housed the mythic past and the technological future.

I longed to return to Hawthornden, as much to write as to push further afield and walk the Pentland Hills. So I did, in May 2001. Shortly before I left the States, Britain’s foot-in-mouth epidemic began, and I arrived to find that walking in any grassy area in Midlothian and the other counties of the Borders, indeed in all of Britain, was prohibited.

The government’s response was, I felt, far worse than the disease itself: mass extinction of livestock and in many cases of a life’s work. The Scotsman reported that farmer suicides were averaging one per week. Trenches were excavated to bury the killed animals, or massive pyres were ignited. Working class people with whom I spoke believed it a collusion with developers to extinguish small holdings as a way of life and bring in agribusiness. In England, where there were so many more farms, dwellers in the countryside stuffed towels and blankets around their houses’ doors and windows to lessen the sickly smell of burning flesh.

At home later that year I watched BBC World News report that as many as 4,000,000 animals had been slaughtered, while acute but usually non-fatal confirmed cases of the disease totaled 337.

This was the backdrop to ‘Quarantine in the Borders.’ Among the poems that emerged from that stay in Scotland, this was one of those written in a deliberately disrupted form.

Notre Dame Review (2008)

Life had, the astrologer said,

but one curse: I could not

go mad.

When I heard the music

I cannot repeat

I was halfway home

five years into the voyage.

Their voices were honey

measure by measure

dropped on the small of my back.

I married the ropes

as well as the mast

my writhing as ranting

a plea as my shouts.

Today I recall not one word.

When I beached I made thanks.

I walked home to the face

without an adventure

to which I was wedded.

(Web exclusive) http://www.bu.edu/agni/poetry/online/2005/gilliland.html

Mary Gilliland lives in the Finger Lakes region of New York and teaches at Cornell. She is a former Stanley Kunitz Fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Recent poems have appeared in LIT, Passages North, Poetry, and Seneca Review. (5/2005)

Walking out of oneself: poetry and labyrinths

Mary Gilliland

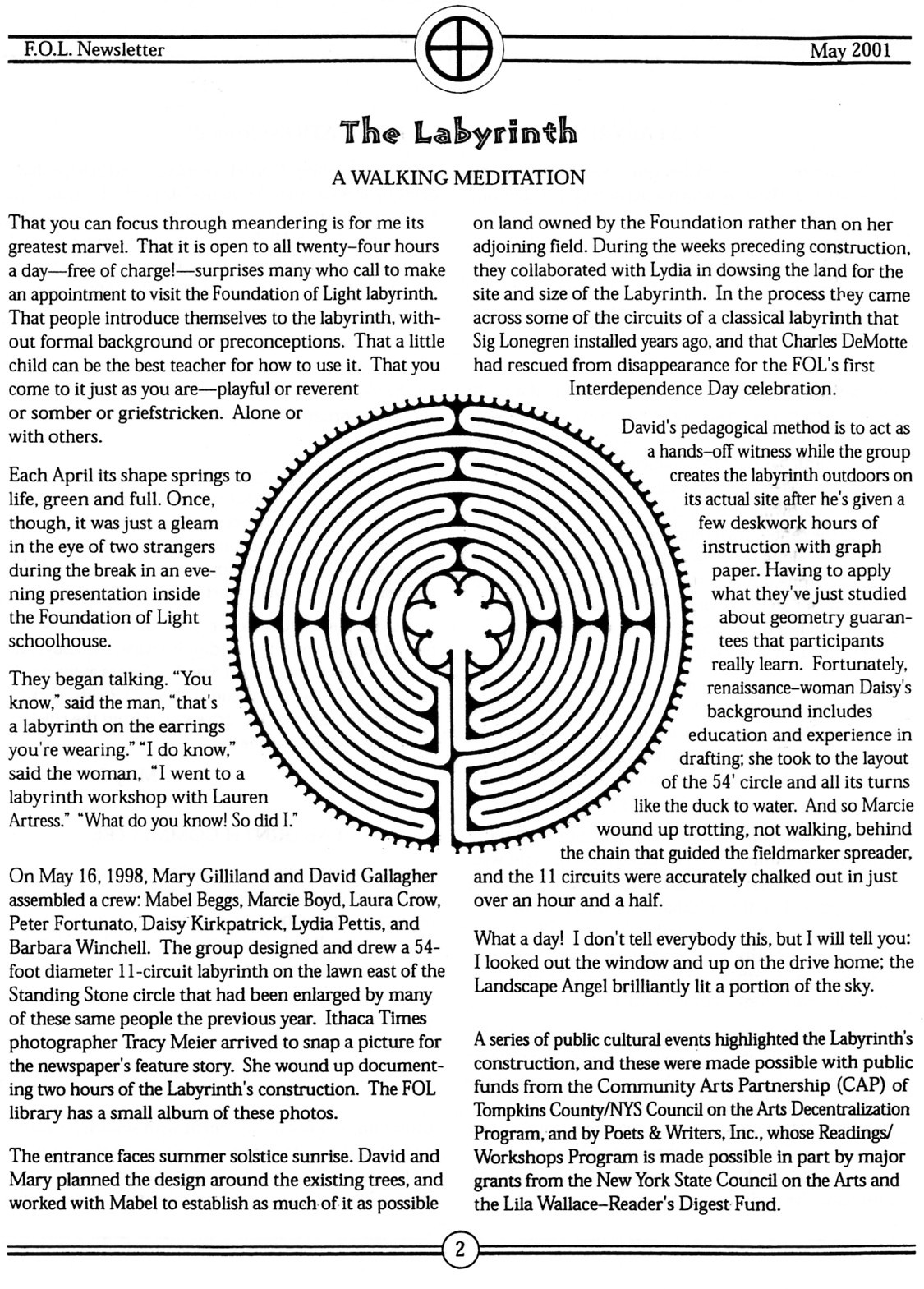

The large outdoor grass labyrinth at the Foundation of Light, adjacent to the circle of standing stones at the northeast corner of Ellis Hollow and Turkey Hill Roads, was constructed on May 16, 1998. Based on the 11-circuit medieval model originally laid in the floor of the nave in the cathedral at Chartres, France, the FOL labyrinth has a diameter of 54' and paths 18" wide to accommodate passage of those walking in alongside those on the passage out. This labyrinth is open to the public 24 hours a day. It has been the locus for many ceremonies and cultural events, and a source of joy, curiosity, and contemplation for thousands of visitors.

Many are familiar with the turf labyrinths and hedge mazes scattered throughout the British Isles. The first historical mention of a labyrinth, by Herodotus, recounts a structure in Africa; the earliest form of certain date is believed to be a clay tablet from Europe: Pylos, 1250 B.C. The symbol is found in Hopi baskets of the Southwest woven with the motif of the man in the maze. The recent usage of labyrinth, however, means a single-path maze. You can’t get lost. The only danger, if such it be, is that you get found.

Art is psychosomatic and it knows when to make its demands. When poets speak of a single work’s gestation, we refer to the sometimes hourlong, sometimes yearslong, search for a match between language, our daily currency, and the priceless source of the realized poem: an intuitive flash, instantaneous; auditory but often nonverbal. Touched, the heart challenges us to unify the twists and turns of a multisensory hunch; our language seeks to align words in such a way that, however complex the material, readers will follow a unicursal path toward a perceived center.

I had been following my particular hunch a long time: a many-sectioned disrupted narrative of domesticity. Incrementally, in the interests of simplicity, I’d cut sections referring to public events and political violence. What do swimming on a Sunday or ridding the garden of woodchucks have in common with the fall of the iron curtain or the bombing of Iraq back into the stone age? Everything, said the poem whose umpteenth draft wasn’t working. Our individual households are dots of dust on a larger household, the globe.

Stone labyrinths were built on the coasts of ancient Sweden and Finland; in medieval Europe the symbol appears in illuminated manuscripts. Poets such as Ovid, Petrarch, and Lady Mary Wroth have drawn the motif of the labyrinth as salvation, entrapment, or development of the soul.

When my internal editor began to speak about all the times the poem had not come right, I told her to hold it. For a few days I reviewed the notes and drafts, the rearrangements, the priorities; both poem and I were ready for the final transcription. Sensing this kind of hunch is as important as sensing the poem in the first place. I promised myself to get started if I woke early enough, by 7 a.m., to get a good chunk done before I had to leave for campus.

The pattern has been decoratively used on a wide variety of human artifacts, from coins to rhytons to printers’ dingbats. The form has even appeared as graffiti carved in a miner’s shaft in Britain. Labyrinths come in different shapes, some circular, some square, and the complexity of the path design can also vary.

The poem had its own plans. I was awake at five, dream in one hand, coffee in the other. I stood at the drafting table, parallel with my favorite tall locust outside the second-story window. Locusts keep their leaves into the autumn. This time the poem knew its own mind; it flowed, no question about it. I’d promised my husband I’d be ready to leave the house by 9 or 9:15, and at 8:45 the last dot hit the page. I got out of the car by the gym and kissed him goodbye, my reward not just a long workout but also the half-hour guided relaxation session that for weeks I’d been vowing to attend. I need a certain tension to compose, but now...hey!

The instructor puzzled over the whereabouts of all the participants from previous weeks; we hardly minded––lucky us, only two. Following his voice we became so still that the world slipped away, as we lay on our backs, knees bent over bolsters, feet solid on the carpeted floor. Instrumental music played softly. From time to time the building’s cavernous ventilation system groaned.

A birthing place for creativity, a map of the imaginal world, the labyrinth is a universal symbol of wholeness found in many of the world’s cultures, from Egypt to China. KMT 9, 1 (1998), a magazine of Egyptology, notes of Sobekneferu (1789-85 BC, last ruler of the 12th dynasty): “She completed the Hawara mortuary temple of the third Amenemhat (known to readers of Herodotus as the ‘Labyrinth’)....Today, unfortunately, that vast structure has been reduced to odd damaged blocks and a waste of sand.” Throughout the centuries and the globe , in turf and in stone, in the visual arts and in literature, walking a labyrinth has functioned as a symbolic representation of life’s quest. To walk the labyrinth is to wind along a clear unicursal path to the center area, then to retrace the same steps outward, guided by the circuit path.

The session seemed as timeless as poetry; at the end, there was some apology for running over, but I didn’t mind, as there was no pressing business at the office. What presses when you’re truly relaxed? I dressed and then walked across Triphammer Bridge, nearly noon, the sun brilliant, the year’s chlorophyll cycle collapsing, the leaves gaining color.

The labyrinth is an archetypal tool for harmonizing movements of the body, turns of the mind, and self-discovery of the human spirit. It is profoundly humane in terms of the mathematics necessary in its design and the aesthetics of its completed form, and like any true cultural artifact its function is to move the heart, kindle the imagination, and inform our earthly journey.

Inside Rockefeller Hall a broadcast was blaring from a professor’s office. Two students sat on the corridor floor, their backs against the tiles, staring at nothing below a bulletin board on the opposite wall. I sensed an odd energy. Oh. Beyond the perceptions I’d been privately enjoying was the rest of the world. But what a day I’d had already, full and centering. I unlocked my office, sorted some papers, turned on the computer.

The phone rang. “How are you?” said my husband’s voice.

“Oh fine. How are you?”

“Oh,” he said. “You don’t know.”

It was September 11. We never do know what the next turn on the path will show us. My solitary poetic feat, completing the disrupted narrative, had synchronized itself with a moment of national vulnerability and grief.

*

As war was declared in the aftermath of the WTC collapse, my friends at Light on the Hill Retreat Center in Van Etten telephoned. Would I give a workshop on labyrinths on October 6, prior to installing one outdoors there, open to the public, for world peace. Using sound and language, we gathered to give simultaneous voice to each part of the pairs spirit and body, terror and peace, divine and daemonic, seeking transformation for ourselves and for our world. After lunch we set thousands of white stones, a gleaming outline, on a high plateau that looks down the Susquehanna Valley into Pennsylvania. Walking the circuits, we had the opportunity to see lives pass before our eyes–both our own and those of others.

The pattern of the labyrinth and its symbolic associations works well with writing, an activity that for many people can become a psychological or emotional maze. The labyrinth replaces the dimension we’re most driven by, time (the minotaur said to be responsible for many of us not writing, or not writing well) with space. When I asked college students in ‘Mind & Memory: An Exploration of Creativity in the Arts & Sciences’ to share with me their thoughts about their writing, some e-mail was nearly as long as the paper it described. I made a composite of the students’ reflections, a legend for an essay. The cuts and pastes rendered individuals anonymous, venerable as a medieval guild, as the legend described the floods and droughts of the writing process, the best thought and the second-thoughts. Each section of the text of their composite reflections about writing matches one of the turns of the classical seven-circuit labyrinth, a place where the walker is shifted by the path to look in a new direction.

Among the series of cultural events funded by the Community Arts Partnership that accompanied the creation of the Foundation of Light labyrinth was a writing workshop at the Moosewood Cafe. Art creates a sanctuary within the everyday; in ‘Litanies & Labyrinths’ I use the most mundane writing we are capable of––a quick list––as foundation for the kind of list that people remember, recite, and pass along to others––a litany. Most moving for me, however, is a return to the oral tradition. At Light on the Hill Retreat Center, after individuals composed two brief texts, each had a partner recite one text while the writer recited the other––simultaneously, and slowly. The rest of us listened to the paired voices. I call this format overtones or voiceovers when I use it for a poem. Many pairs had a paradoxical or even conflictual relationship with each other, which seems to me an accurate representation of the multiple thoughts, wishes, identities that each of us contains.

*

In an eleven-circuit labyrinth such as the one at the Foundation of Light, the path meanders throughout the whole circle. There are 34 turns on the path going in to the center. Depending on the pace, the walk to the center can take 45 minutes or 5; the spirit of the walk can be serious or playful. People often walk in groups, following the same path but in different locations on the circuits, developing both individual awareness and a sense of community.

As labyrinths spring up across the United States in hospitals, churches, community centers, private lawns, fields, I have pondered the revivified tradition of seeking, walking, and building them. They seem a contemplative and collective antidote to an increasingly tense, fast, and overly individualistic way of life. People use them at times of uncertainty, when facing an important decision, for healing emotional wounds, during illness and bereavement, when awestruck by joy. To walk a labyrinth can be an act of praise, thanksgiving, mourning, festivity, prayer, rejoicing, inspiration, hope. One of the best teachers of labyrinth use is a three-year-old, for in addition to walking, one can also skip, run or dance. A labyrinth can facilitate a state of calming, energizing, finding what you’ve always looked for, facing the unexpected, allowing the path ahead to become clear.

I’ve been privileged to participate in making three of the many labyrinths in our area, including the one that our geometric genius loci, David Gallagher, installed at Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies. My file holds correspondence and calls with arts councils, churches, colleges, healing and recovery centers, and private individuals from various parts of this country, many of whom took a guided walk or visited the Foundation of Light Labyrinth in order to create their own elsewhere. Late October brought an e-mail: “Hi, I wrote about your Labyrinth on pages 89-90 of the just-released guidebook Eccentric America. Thought you might want to know.––Jan Friedman.” The book is subtitled ‘The Bradt guide to all that’s Weird and Wacky in the USA.’ Well. Now I know. I wish our many other labyrinths had made the list, for at the rate they’re proliferating, it will soon be time for a Finger Lakes Labyrinth Trail.

*

I was teaching during the Columbine high school massacre. Al-Qaeda has more resources and a bigger network but the mind to me seems similar to that of those sorry teenagers, in its aim to destroy the existing world and create another. We all go about creating another world to live in; that––individually and collectively––is our fundamental problem as human beings. Think of creation myths that chart the fall, the memory of the ideal life. Think of a few hours or a few days from now, your plans for.... But imagination is also our joy. We long for pattern, for a form to hold our slurry. So, if our consciousness has not evolved past generating mental constructs that separate us from the world we live in, we can literalize the separation. Measure it, mark it. See it. And walk it.

And love it. It is so becoming, our path. Let us become one with it. We do not know what tomorrow will bring. Or today. The shape of the labyrinth creates a symbolic, resonant space to use in daily life. Like a work of art, its function is to go beyond what you expect. And in doing so, to bring you to what you truly know.

Mary Gilliland is a poet who lives in Ithaca. For descriptions of her labyrinth writing workshops on Saturday, December 15, contact her at mg24(at)cornell.edu or 273 6637.

________________________

Upon the death of loved ones we often notice a

transparency in the borders that normally seem to separate the spheres

of existence. Their favorite unusual bird may hover in the vicinity of

the living; their mirror may slide from its hook to the floor. I am one

of many siblings and the first of us to die was not quite forty. After

my brother Tom’s funeral in early 1999, I deeply missed our sensory

contact, and wished for it aloud. Between that evening and next morning

three epiphenomenal electrical events occurred in my motel room, including

a recurrent blinking light on the telephone’s message button. I

would raise the receiver, call for my message, listen to the silence,

and then hear the recording “your message has been received.”

Tom had lost his life but not his sense of humor. After death, it is as

though the energy contained in one body has been released for the awareness

of all beings. The two triangles that form the symbol of the Dharmodaya

are one.

During the June 2002 retreat in New York City, Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche

reminded us that when placed on the dying, tag drol creates a cause for

their joining the Dzogchen path. Tag drol means liberation through contact,

through touch. Some years ago, at the end of a Ganapuja held before he

departed from New York following treatment for leukemia, Rinpoche gave

a tag drol to each of those present, a miniature paper mandala on which

are inscribed hundreds of empowered mantras. He also gave each of us a

packet of powder called chin lab, meaning ocean waves of the blessings

of the teachings, the empowering energy of the lineage. The powder is

made of things from Rinpoche’s own teachers. He taught us that these

two objects are especially helpful for the dying. Placed on the head,

they connect the person with enlightenment here in the Nirmanakaya.

I have had several occasions to use the gifts that Norbu gave us for those

in need, and one of these was as my brother moved toward death. He had

been ill for seven years. Following his last, and merely palliative, surgery

for ogliodendroglioma he was discharged, upon his prior request, to rejoin

his wife and children, to die at home. He had been in coma about ten days,

and the surgeon would give my sister-in-law medications for only 48 hours

since in his view that was more than enough. It was a somber gathering

of family and siblings who had traveled long distances; at bedtime I took

the first watch.

I placed the tag drol and a bit of the chin lab on Tommy’s head

and then a large chunk of crystal from Tibet on his chest, of the type

known as self-healing because of the way it was formed. I told him what

I was doing, where he was, what had happened. I talked about how much

love surrounded us, and that whichever way he chose to go was okay. Feeling

my own emotions and those of the sleeping household, I took a long time

with these prayers for all of our letting go. Then I settled into my chair.

I felt like putting the blanket that draped my shoulders over my head.

It was winter. It was dark.

Of the eight siblings, Tom got the blue eyes. Two hours later I looked

up to see those eyes staring at me, with expression. ‘Mary,’

he whispered urgently, ‘I have to go.’ ‘You have to

go?’ I said, from the realm of grieving metaphor. ‘Yeah. I’m

thirsty. And I have to go!!!’ ‘It’s okay,’ I said,

realizing what he meant, ‘just go. You’re catheterized.’

For perhaps half an hour I could see consciousness reassemble in his eyes,

in his face, as we talked. At one point I asked where he had been during

those days in coma. ‘I was in God’s heart,’ he said;

then after a pause, ‘I was in God’s belly.’ For three

weeks a miracle unfolded. With the use of only his face and one hand free

of bodily paralysis, he dispensed love, comedy, memory to those present.

One day his wife, who is a nurse, took him to a hospital for rehydration.

They insisted on an MRI as well, and declared (a bit huffily, according

to Marie) the man should not be alive, as his breathing reflex had been

destroyed in the surgery that had taken place next to the brain stem.

Tom made it though the Christmas holidays and his son’s thirteenth

birthday before moving on.

‘Most important is not [that] you are integrating in a calm state.

That is easy. For everybody. Most important is you are integrating with

movement. Then you are educated. You can integrate more in daily life.’

These words are among my notes from Norbu Rinpoche’s teachings in

New York City on Friday, the day before he transmitted the lung of many

practices, communicating their syllable in the ear of his students. A

retreat increases the capacity of our practice; our challenge when retreat

is over is to apply the teachings. On Sunday, both humorous and poignant

in tracing the possible foibles of our intentions, Rinpoche prepared uss

for reentry to our daily lives: ‘In our idea….how I like this

practice and one day I will do. But that famous one day….Our lives

are very busy. And so pass months, years.’

Being with the dying has brought me moments beyond measure. But measure

applies to every moment I am living, when time and obligations seem so

pressing. The day for practice is today, for I may never see another.

Like malas and thankgas and other sacred objects used in our practice,

tag drol and chin lab help to increase awareness of our intention and

our circumstance. Life is not infinite, but it is boundless.

first published in The Mirror, 2002

This article originally appeared in The Mirror 61, May/June 2002>> Top of page