| IPM table of contents |

| Regulatory control |

| In this section:

|

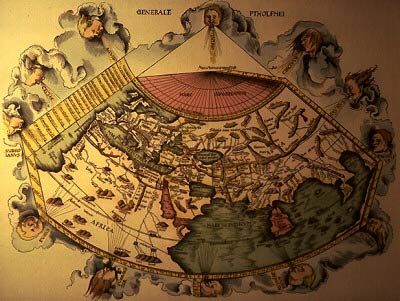

Over the centuries, human beings have carried desirable plants with them as they migrated around the world. Today most of our crop plants are being grown where they are not endemic. In many cases we have been successful in introducing the crop species without carrying along some of their pests, and we have been selecting crops for perhaps hundreds of years in the absence of many of their original pests. Since we have not been selecting for resistance to these pests, some of the crops have lost what resistance they may have had to their ancestral pests. Many of our crop plants are now uniformly susceptible to endemic pests of their ancestral stock. (For example, most potato varieties are susceptible to the golden nematode.) Opportunistic pests. Some introduced pest species are opportunists–capable of attacking host plants with which they have not coevolved. As a result, the host plants have not evolved defenses to these pests (e.g., the American elm and the Dutch elm disease pathogen, Ceratocystis ulmi). Likewise, predators, parasites, and competitors may not be well adapted to an introduced pest (such as with the gypsy moth). Consequently, many introduced species that were minor pests in their native habitats have become major, invasive pests in their new habitats. Quarantine reestablishes barriers. High-speed transport increases the likelihood of successful transport of short-lived pests. Physical barriers to the spread of pests (oceans, mountains, deserts, etc.) have been breached by the rapid transportation of people and goods and the international movement of seeds, planting stock, and soil. The purpose of quarantine is to reestablish these barriers and to restrict movement of pests into areas where they do not occur. Quarantine involves reducing the risk of pest introduction through the application of specific technical measures within an established legal framework. International trade agreements recognize and support the sovereign rights of nations to protect their agriculture and their natural resources from the introduction of harmful pests, and these agreements generally contain provisions for quarantine. These same trade agreements also attempt to prevent countries from using phytosanitary restrictions as disguised trade barriers. International organizations involved in quarantine The International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) is the internationally recognized organization responsible for setting phytosanitary standards and coordinating plant protection around the world. The IPPC has established guidelines for national and regional cooperation in plant quarantine and phytosanitary procedures. Regional plant protection organizations (RPPOs) have been created to coordinate phytosanitary efforts within their respective areas.

The RPPOs cooperate inter-regionally and also provide technical assistance to the national plant protection organizations within their respective regions, exchanging information and helping them to establish phytosanitary measures consistent with international standards. National organizations involved in quarantine Nearly every nation of the world has its own national plant protection organization, and nearly all are signatories to the International Plant Protection Convention, agreeing to adhere to its provisions. As an example of how a national plant protection organization functions, we will use the Plant Protection and Quarantine Program (PPQ) of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service ((APHIS)) . APHIS formerly is a unit of the United States Department of Agriculture, that collaborates with the Department of Homeland Security. APHIS/PPQ functions in close collaboration with the IPPC and NAPPO. APHIS/PPQ uses a systems approach to reduce the risk of introduction (or establishment) of a pest. They evaluate the risk of introduction from various sources, quantify the effectiveness of various risk mitigation measures, and employ a combination of such measures. The goal is to have at least two independent measures that have an additive effect in reducing the risk of introduction of a pest. Developing specific measures for a particular pest involves input from the grower (seller), the shipper, the buyer, state regulatory officials, agricultural experiment station researchers, and the growers that would be affected by the introduction of the pest. There are four lines of defense in risk mitigation: 1. Point-of-origin. Minimize the occurrence of the pest in the product to be shipped. APHIS/PPQ works with the producers to develop and implement the necessary pest control measures, inspects the crop in the field, and issues phytosanitary certificates for the crops that meet the risk mitigation criteria. APHIS/PPQ also works with and certifies the major packers and shippers.

3. High risk zones. APHIS/PPQ monitors for specific pests and conducts field inspections in areas where there is a high probability of detecting newly introduced pests (usually around points of entry). A good example is monitoring Mediterranean fruit fly introductions in California, Texas, and Florida by means of sex pheromones and bait traps. The purpose is to detect low populations well before they are established and while they can be eradicated. 4. Regional inspection program. In a program called the Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS), APHIS/PPQ works closely with the research and extension personnel in the state agricultural experiment stations to monitor pests and biological control agents in the nation’s major crops. By collaborating with the expert observers who are in the field almost daily, CAPS attempts to detect introduced plant pests before they become well established. The challenges of quarantine Quarantine is most effective where there are physical barriers to help keep the immigration of pests to a manageable level. Oceans, mountains, and deserts generally are effective barriers to pest movement, and historically the time required for humans and cargoes to traverse these barriers and the limited points of entry helped to reduce the numbers of new pest introductions. But in these days of high-speed transport, a pest can be transported thousands of miles in only a couple of hours, rendering these physical barriers ineffective. Furthermore, political boundaries do not always correspond with physical barriers, and the pests do not respect legal border crossings. Consider the enormity of the job:

No wonder pests slip through. Every quarantine program must be prepared to mobilize an effective eradication campaign quickly, and every pest management program that relies on quarantine as a major tactic must begin to prepare for the possibility that the pest cannot be eradicated and will become established. At the very least, an effective quarantine buys time to develop alternative control measures. Once the pest population becomes well established in the quarantine area and eradication is out of the question, the quarantine is no longer useful.

|

© Cornell University 2003