|

|

|

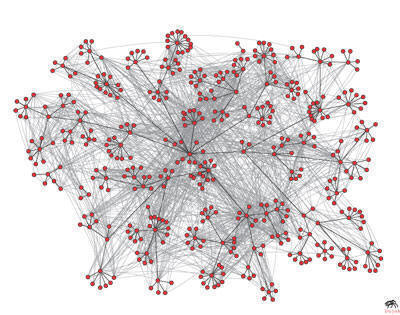

Networks

Economics 2040 / Sociology 2090 / Computer Science 2850 /

Information Science 2040

Cornell University, Fall 2016

Mon-Wed-Fri 11:15-12:05

Statler Auditorium

David Easley

(Economics) and Eva Tardos

(Computer Science)

Note: This is

not the current semester's course Web page. For current course information,

handouts, and homework assignments, please visit the present semester's

version of the course.

A course on how the social, technological, and natural worlds are connected, and how the study of networks sheds light on these connections. Topics include: how opinions, fads, and political movements spread through society; the robustness and fragility of food webs and financial markets; and the technology, economics, and politics of Web information and on-line communities.

The course is designed at the introductory undergraduate level with no formal prerequisites; it satisfies the Arts & Sciences Social and Behavioral Analysis (SBA) distribution and the Engineering Liberal Studies (SBA group) distribution.

Course Staff

- Instructors:

- David Easley, 434

Uris Hall, dae3

- Eva Tardos, 316 Gates Hall,

et28

- Head TAs

- Hedyeh Beyhaghi, hb377

- Fikri Pitsuwan, fp67

- Course Staff:

- Abenezer Mulugeta,

aml382

- Austin Lin, aml276

- Brad Tiller, bjt79

- Christie Wang, cw584

- Eric Schulman, ehs82

- Jacqueline Law, jjl284

- James Cramer, jcc393

- Jatin Bharwani, jsb399

- Leke Ojo, omo5

- Marta Maksymyuk, mm2556

- Michael Huang, mxh2

- Prajjalita Dey, pd292

- Pravir Samtani, ps795

- Rohit Bakshi, rhb255

- Saakshi Singhal, ss992

- Tori Feigeles, taf78

- Wilson (Seung-Won) Yoo,

sy536

CMS

Site

At the CMS site,

you can log in with your Cornell NetID to find

information about your course grades and also to upload solutions to homework.

Solutions to all problem sets must be submitted through the CMS site. The site will require files to be in PDF format. Also, you should check the CMS site at the start of the semester to make sure that you are able to log in. Please let us know if you experience any difficulties with this.

Class

Blog

We will be maintaining a class weblog as part of the course,

and posting to the blog will be part of the graded coursework, as will be

described in the accompanying handout. For

instructions on how to ask permission to post, please read the opening

blog post.

Class

Discussion on Piazza

We will be using Piazza as a discussion forum for the class.

Feel free to post any questions you have about class. Only students and

instructors in the class will be allowed to post to it, and students and

instructors and TAs can all answer questions. To get started, please add

yourself to the class

piazza page as a student using your @cornell.edu email address.

Materials

- We will be using the book Networks, Crowds, and Markets

(Cambridge University Press, 2010), which we wrote while teaching this

course over the past several years. A complete draft is on-line at the Web page for

the book, and the hardcopy version is for sale at the Campus Store.

- For the past two years, we've offered an on-line

version of the course through the edX

platform. The materials from this course are now archived, and you can

access them by registering on-line at the edX

site. Although you can no longer take the edX

course as a student, by registering you get access to the videos and

on-line exercises. In the course this fall, this edX

material will serve as a set of optional resources that you may find

helpful for alternate presentations as well as a source of additional

practice exercises.

- We'll use clickers in lecture. Please register your

clicker on the CIT website. You must use a clicker from the i-Clicker

system. Academic integrity guidelines require that you may only use your

own registered clicker during class.

To register your i-Clicker: Go to http://atcsupport.cit.cornell.edu/pollsrvc/ . Log in with your NetID and your password. Click on the link "Click here if you wish to submit a request for [yourname]". Type in the clicker ID# and click "Submit". At that point you have successfully registered your i-Clicker with the Cornell i-Clicker system. Please do not register iclickers at the iclicker.com site.

Office

Hours

- Mon 1:00 - 2:00:

Abenezer or Eric, G15 Gates Hall

- Mon 4:00 - 5:00: Jatin

or Fikri, G15 Gates Hall

- Tue 1:30 - 2:30: Prof.

Easley, 434 Uris Hall

- Tue 3:00 - 4:00: Tori or

Leke, G11 Gates Hall

- Wed 3:00 - 4:00: Prof.

Tardos, 316 Gates Hall

- Wed 4:00 - 5:00: Saakshi

or Prajjalita or Hedyeh, G11 Gates Hall

- Wed 6:00 – 7:00:

Marta or Austin, G15 Gates Hall

- Thu 3:00 - 4:00:

Jacqueline or Pravir, G11 Gates Hall

- Thu 4:00 - 5:00: Wilson

or Michael, G19 Gates Hall

- Thu 5:00 - 6:00:

Christie or Brad, G19 Gates Hall

- Thu 6:00 - 7:00: Rohit

or James, G15 Gates Hall

Final exam will be available for inspection

December 14-15 during the hours of 12:30-4pm in the handback room: Gates

216.

Outline

of Topics

(1) Graph Theory and Social Networks

The course begins with a discussion of some of the general

properties of networks. It develops this through examples from social network

analysis, including the famous ``strength of weak ties'' hypothesis in

sociology, and it connects these themes to recent large-scale empirical studies

of on-line social networks.

Readings

- Chapters 1-3 and

Chapter 5.

Optional further reading:

- Mark Granovetter. The

strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78:1360--1380,

1973.

(This

is Granovetter's original paper describing his work

covered in Chapter 3 of the Networks book.)

(2) Game Theory

Since most network studies require us to consider not only the

structure of a network but also the behavior of the agents that inhabit it, a

second important set of techniques comes from game theory. This too is

introduced in the context of examples, including the design of auctions and

some ``paradoxical'' phenomena surrounding network traffic congestion.

Readings

- Chapters 6, 8, and 9.

(We will cover Chapter 7 later in the semester.)

Optional further reading:

- Ignacio

Palacios-Huerta. Professionals

Play Minimax. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2003), pp. 395-415,

(This

is the paper that studies penalty kicks in soccer, as discussed in Section

6.8.)

(3) Markets and Strategic Interaction on Networks

The interactions among participants in a market can

naturally be viewed as a phenomenon taking place in a network, and in fact

network models provide valuable insights into how an individual's position in

the network structure can translate into economic outcomes. This provides a

natural illustration of how graph theory and game theory can come together in

the development of models for network behavior. Our discussion in this part of

the course also builds on a large body of sociological work using human-subject

experiments to study negotiation and power in networked settings.

Readings

- Chapters 10-12.

(4) Information Networks and the World-Wide Web

The Internet and the Web of course are central to the

argument that computing and information is becoming increasingly networked.

Building on the earlier course topics, we describe why it is useful to model

the Web as a network, discussing how search engines make use of link

information for ranking, how they use ideas related to power and centrality in

social networks, and how they have implemented network-based matching markets

for sellling advertising.

Readings

- Chapters 13-15.

(5) Network Dynamics: Population Models

Networks are powerful conduits for the flow of information, opinions,

beliefs, innovations, and technologies. We begin by considering how these

processes operate at the level of populations, when we can't necessarily

observe the network itself, but only its effects on aggregate behavior. As part

of this, we consider phenomena including information cascades, "tipping

points" in the success of products with network effects, and the

distribution of popularity.

Readings

- Chapter

7, Chapters 16-18, and Chapter 22.

(6) Network Dynamics: Structural Models

We continue our exploration

of how things flow through networks, focusing on what we can learn from details

of the network structure itself. Here we study how both behaviors and diseases

can spread through a social network, and also some of the network phenomena

that underpin the "six degrees of separation" effect.

Readings

- Chapters 19-21.

Optional further reading:

- Michael Suk-Young Chwe. Structure

and Strategy in Collective Action. American Journal of Sociology 105(1999),

pp. 127--156.

(7) Institutions and Aggregate Behavior

Finally, a perspective based on networks can provide novel

insights into the structure of social institutions, and into basic policy

questions in many areas. We illustrate this theme with examples based on

markets, voting theory, and property rights.

Readings

- Chapters 23-24.

Prerequisites

Almost no knowledge of specific mathematical content is assumed, other than some basic probability (random variables, expectation, independence, and conditional probability), which we will briefly review when it first arises.

The main goal of the course will be to build mathematical models of the processes that take place in networks. As such, students will be expected to interpret and work with mathematical models as they come up the course; at the same time, students should also think about how to relate these models to phenomena at a qualitative level.

Coursework

- Midterm: Wednesday, October 5th, in class.

- Final exam. Thursday,

December 8, 9am

- 9 problem sets. As described above,

these must be submitted using the CMS site,

by the start of class on the days they are due.

- Class blog: There is a class weblog, and each student

should make three posts to it as part of the graded coursework, following

the details will be described in the accompanying blog guidelines.

- Grades on the homework, blog posts, midterm, and final

will be weighted as follows:

- Homework: 36% with the

lowest grade on a homework dropped.

- Midterm: 20%

- Final Exam: 35%

- Blog Posts: 9%

- iClicker participation: 0% (may

have a tiny effect in borderline cases)

Academic

Integrity

You are expected to maintain the utmost level of academic integrity in the course. Any violation of the code of academic integrity will be penalized severely.

You are allowed to collaborate on the homework to the extent of formulating ideas as a group. However, you must write up the solutions to each problem set completely on your own, and understand what you are writing. You must also list the names of everyone that you discussed the problem set with.

Collaboration is not allowed on the other parts of the coursework.

It is not admissible to use resources beyond course material and student discussions for solving homework questions. In particular, you may not use Wikipedia, or search the Web, or look at any textbook, other than the one assigned in the course. Using such additional resources to solve homework problems is a violation of academic integrity.

Finally, plagiarism deserves special mention here. Including text from other sources in written assignments without quoting it and providing a proper citation constitutes plagiarism, and it is a serious form of academic misconduct. This includes cases in which no full sentence has been copied from the original source, but large amounts of text have been closely paraphrased without proper attribution. To get a better sense for what is allowed, it is highly recommended that you consult the guidelines maintained by Cornell on this topic. It is also worth noting that search engines have made plagiarism much easier to detect. This is a very serious issue; instances of plagiarism will very likely result in failing the course.